How to write amazing Bullet Points

Learn about the Levels System: the framework I developed to write amazing bullet points. Follow this 5 steps checklist to rank your resume within the top 1%.

Posted on June 20, 2025

Last updated: October 16th, 2025 | 20 min read

I spend a lot of time on answering questions about resume writing, job searching and interviewing.

One that comes up a lot is how to interview well, and more specifically how to answer the open-ended questions (often asked at FAANG, etc…). There’s mostly generic/vague advice online, which you probably found hard to apply.

So I wrote this step-by-step guide with everything you need to know on the topic. This is an article you can keep referring to, so you can get better at this skill which will serve you for your entire career.

This method is based on my 12 years recruiting experience, especially for Google, where I part of my job was to analyze interview performance.

Here’s what you'll find:

Ready? Let’s go!

The purpose of an open-ended question is not to get a final answer. It is to get a thought-process.

You're forced to expose your actual chain of thoughts, because:

The experience can be nerve wrecking, especially if you're new to it. You're already in a stressful situation (interviewing), and you're essentially asked to improvise. You have to think about the answer and communicate it at the same time, which is a lot for your brain to process so it removes all posturing. You're exposed and you have no other choice than to reason out loud.

These interview questions are much more telling than “Where do you see yourself in 5 years?” 😉

So what do these open-ended interview questions actually look like? They come in 2 flavors: behavioral (also called hypothetical) and situational.

Behavioral questions are based on past experiences. Their goal is to trigger the memory of an event, which you will then articulate as an answer. By walking the interviewer through what happened, you expose your behavior in a certain context.

They often start with Tell me about a time when… Here’s one:

“Tell me about a time when you opposed your managerial decision?”

That's a classic question used at FAANG to evaluate someone's ability to do what's best for the company despite the hierarchy. This fits Amazon's "Have Backbone" principle, or Google's "Do The Right Thing" rubric.

Situational questions are made-up scenarios. They’re in my experience the hardest to answer, because the context could be totally unfamiliar to you. It’s like a simulation lab.

Here’s the hypothetical twist on our previous question, so that you can see the difference:

“Your manager just made the decision to which you disagree. What do you do?”

The context is much narrower, so that situation likely hasn't happened to you yet.

Typically, competitive companies (FAANG, etc…) will use both types of questions during the same interview, so that they can confirm that past behaviors are consistent with potential (future) behaviors.

Even though these 2 types of questions may feel different, the methodology and assessment are the same.

Understand that big companies take interview questions extremely seriously. FAANG have detailed interview questions repositories with vetted questions to select from. Questions sometimes require approval from the recruiter so that interview feedback is deemed valid. I am not joking: I have had cases where new interviews had to be redone because the wrong set of questions was selected. (nope, candidates weren't happy...)

It also not just one question: they are also pre-calibrated follow-up questions. They do this to stress-test your plan and to allow you to elaborate. You will give you first "main" answer, and the interviewer will guide you through digging deeper.

You shouldn't see these follow-up questions as a challenge, unless you're forcing the interviewer to ask basic questions on obvious details. They're mostly here to help. My advice is to think of these interviews as a conversation, rather as a Q&A.

Smaller organizations may be less sophisticated, but my advice is to prepare as you would for a top player.

This section is super important, because once you understand how you're evaluated, it will make everything else much clearer.

I can't go over the specific evaluation rubric of each company, and I don't need to. They all tend gravitate around 3 components: Structure, Complexity and Logics.

Let's go over each of them in detail, so you can visualize the interviewer's checklist.

The most obvious part is structure, which comes down to these 4 questions

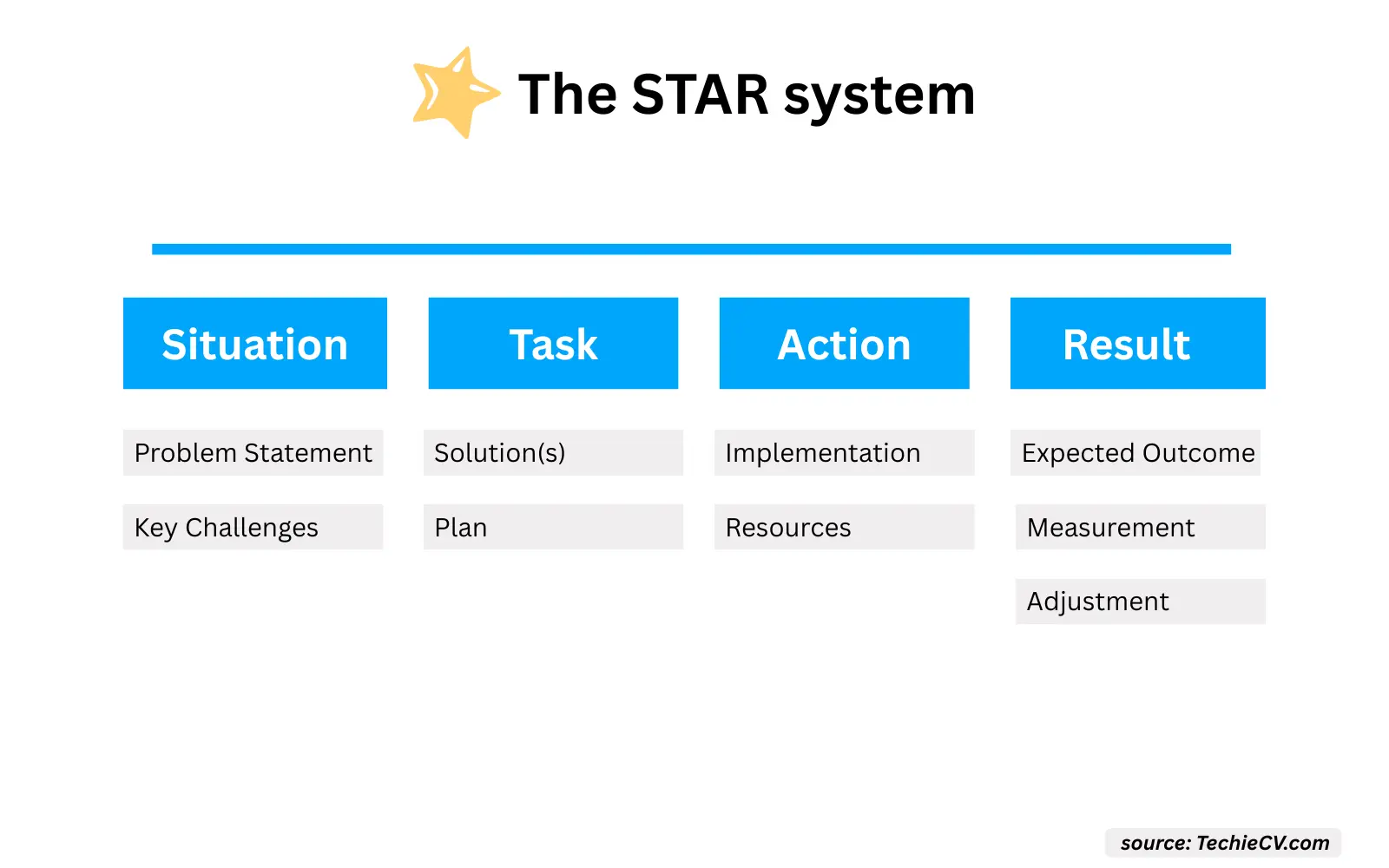

You've probably heard of the STAR method, which helps you organize your answer in successive steps.. That part is actually well covered online, so I won't elaborate on it with this article. No myth busting here: it does work. Unfortunately though, most of the general advice stops here. But we'll go much deeper 😉

During my previous career as a recruiter, I had to analyze and document interview feedback to support candidates in front of hiring committees. What I found is that most candidates understood the structure part, and most of the difference was made by their ability to handle complexity.

During interviews, complexity is 3 components:

Each of these bring an additional dimension to the basic structure, which creates more depth to your answer. This is the part top candidates nail.

The last part is the quality of your reasoning itself. There are 2 components to it, which I'll call critical thinking and support.

Critical thinking is your argumentation. It's whether you made reasonable claims or statements based on the given context. Are you solving the right problems and making relevant hypotheses?

Support is your ability to back your hypotheses. It is a bit tricky: on your resume, you're told to quantify achievements with metrics, but with open-ended questions you won't have those.

Interviewers need to see that you can deduce/infer useful data, or use logical statements to confirm your claims. In the more abstract cases (like the Q&A example at the end of this article), you should at least explain why an action should lead you to the desired outcome.

For more concrete cases (especially for situational questions), you can support your argumentation with past examples, which is what my “Story bank” technique (see below) is perfect for.

Now that you know what you're up against, let's begin your training, young Padawan! 🏋️♂️ how do you actually prepare for these, if you don’t know which question will be asked?

I'll give you the method that got me my job at Google, which I kept recommending to candidates.

The key is to train a thought process, instead of specifics answers. The best way to get better at this is to focus on each aspect (structure, complexity, and reasoning) individuallyfirst, before putting it all together.

I'll give you an exercise, with **3 levels** you can clear.

For the structure, you need a framework that will help you organize the steps of your problem solving.

The most well-known is STAR (Situation > Task > Action > Result), but there are others (PAR, CAR, SOAR, etc…). They’re all essentially the same thing: pick one. What matters is that you can visualize the steps.

As a quick reminder, here how you should think of it:

Here's the Exercise:

This will eventually help you internalize the structure and instinctively think in terms of steps. This is essential to free up cognitive load, so that you can focus your brain power on complexity and reasoning, rather than structure. I did not invent it: this is how musicians prepare for improvisation. They "hard code" scales, patterns and musical phrases, which then come out naturally so that they can focus on creativity on stage.

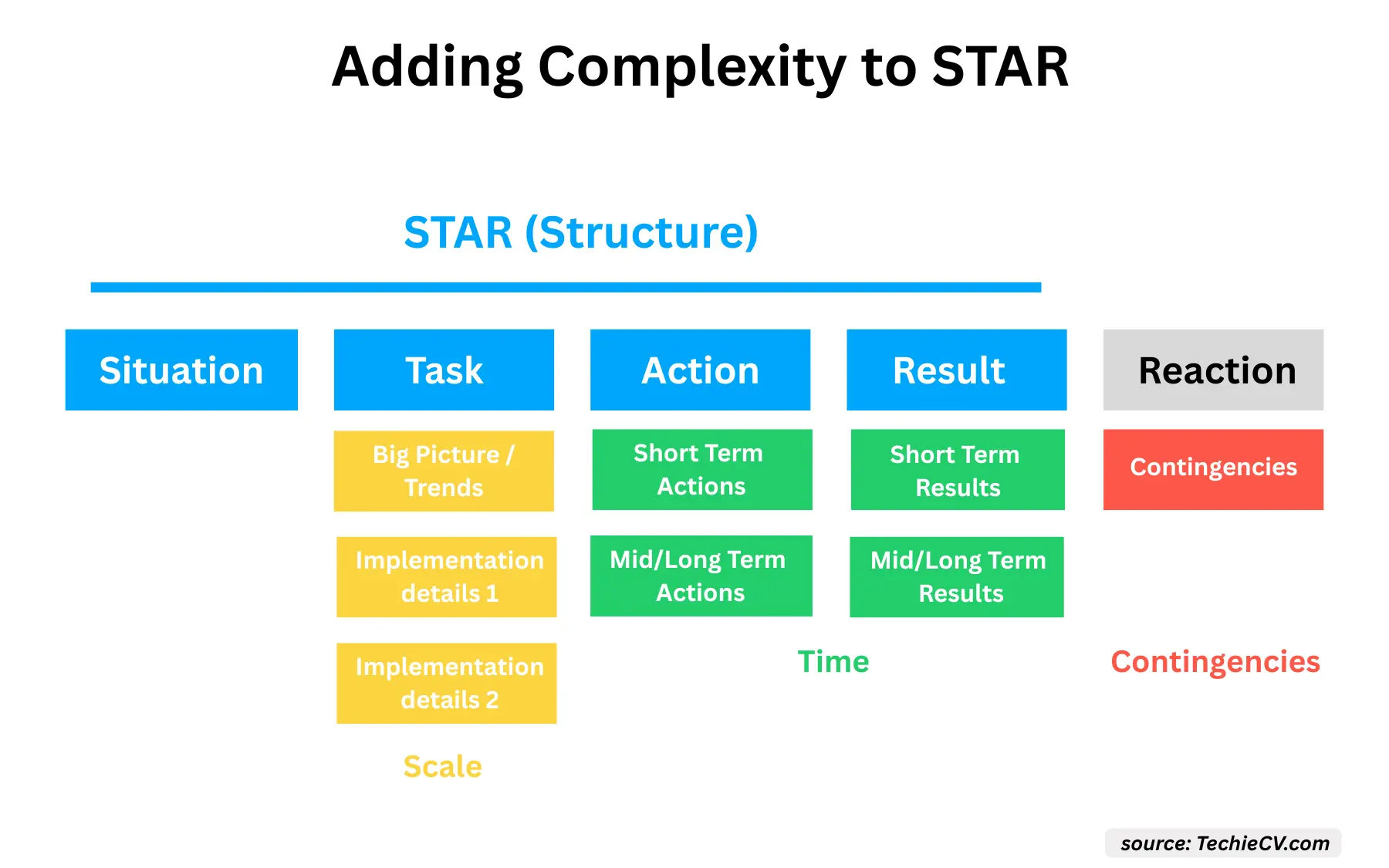

Training for complexity is a bit harder, because it's less linear. I made a simple diagram to show you where each of the components would fit within the STAR structure (see below).

To train on this, use the the same exercise as before, but this time, add more details on one of the 3 components of complexity (Time, Scale, Contingencies).

Work on timeframe first: you can think of that as adding several Action > Result loops (for short term, then mid-term, then long-term) instead of the unique one you had within the original STAR structure.

Then focus on scale, which fits best within the "Task" step. You can split it into (i) the overall strategy and then divide it into (ii) 2/3 areas of implementation. There's no limit to how complex you can go with creating more "sub-parts", but start by using the simplest version possible first, and complexify later.

Once you're comfortable with timeframe and scale, add the contingency part after the Result step of your STAR system. You should ask yourself "What could go wrong?" and answer the 1/2 first issues that come to mind with (a) problem statement, (b) solution, and (c) expected result.

It's hard to train your reasoning with a specific technique. Doing the exercise itself trains that muscle and you should find logical connections more quickly over time.

Here's are the 3 ways to handle the support part:

Because the interviewer wants to uncover past behavior, you have to come up with stories to illustrate the cause and effects. This brings a new problem: how do you think of the right story on the spot?

When preparing for my Google interviews, I built what I called a Story Bank, and I then recommended candidates to do the same. Here's how it works:

While training on situational questions, you'll realise that even if they're all different, they cover the same list of topics (types of behaviors). Topics that come up often are: conflict management, acting as a owner, taking & giving feedback, challenging authority, communicating clearly/adapting messaging, creating resources, etc...

Once you know that, you can prepare a couple of past stories for each topic, and train on communicating these. During the interview, you can just call in the right story at the right time. Because you will be trained on these, your delivery will become excellent, and you can test/swap/improve them from one interview to the next.

This makes situational questions easier to get right over time 😁

Before reviewing a concrete example together, I wanted to give you 4 techniques I use to give candidates to improve their performance. Once you're comfortable with the training above, you can start adding them to improve your game even further.

If you follow the STAR method, you know that assessing the situation (the problem at hand) is the first step, and follow up questions are a great tool to gather information.

2 small tips:

You might need to use metrics, volumes, scales, proportions, etc in your answer, for which you don't know real world numbers. If that's the case, make assumptions and tell the interviewer that "your reasoning takes X as a base to measure Y". >Again, they evaluate you on your reasoning, so the actual number doesn't matter.

The third advice is to take your time to answer. Interviewers do not expect you to answer within seconds, but when it does come they do expect your thoughts to be organized. It also helps with perception: someone who pauses before answering appears more thoughtful than someone who rushes to answer.

Don’t try to build the whole answer in your mind before answering. Instead…

(1) Create a rough plan in your head. (2) Then walk the interviewer through your reasoning while adding complexity. Yes, it's a hard gymnastic to handle without experience (hence my training recommendation above), but once it becomes natural it reduces cognitive effort. You get the best of both worlds: a well-thought out structure (prepared mentally), and complexity + quality of reasoning (thought “out loud”).

So... after all that theory it's time to give you a concrete idea of a good answer. We’ll use my favorite hypothetical question (Yay!).

“You've been working on a mission-critical project for 6 months and you're suddenly asked to hand it over to a colleague. What do you do next?”

{SITUATION - Problem Statement} I believe they are 2 problems to address here: first the reason for the handover, then make sure it happens in the most efficient and safe way, while maintaining team cohesion.

{SITUATION - Follow-up} Did the handover happen because of my own performance issue or because of external factors?

(let's say the interviewer answers that it was because "your manager was unsatisfied with your performance.")

{TASK - Scale: Big Picture View} You mentioned that the project is mission-critical, so the focus should first be on ensuring a smooth handover (short-term), before analyzing my own performance in detail (mid-term) and working toward a (long-term) upskilling plan.

{TASK + ACTION - Scale: Granular details / Timeframe: Short-term}

Here are the actions I will take during the first couple of days:

I'll first ask for direct feedback from my manager to identify the basis of the decision. This is the surest way to understand key mistakes or shortcomings. I'll also schedule a conversation with them to hear their detailed assessment of my performance in these areas in comparison to their expectation. This will give me an idea of what to strive for, and how far I was from it.

I'll then request feedback from all collaborators specifically on the areas to be improved, to understand how it impacted their work with specific examples. It should allow me to internalize how important success in the area is.

For the sake of this argument, I'm going to assume that the feedback is that I was too slow in making decisions, which created a bottleneck and stakeholder frustration, while risking timely delivery.

So, during the following days...

I will communicate my mistakes and stakeholder feedback to my colleague so that they understand the context and prior issues. I'll stress that speed is crucial and that they should keep a sense of urgency.

I will organize key information and resources to handover rapidly so that project timelines aren't impacted further, and I will introduce them to key stakeholders rapidly.

I might help them formulate a new plan if they assess that they need my input or more context from me.

{TASK + ACTION - Scale: Granular details / Timeframe: Mid-term}

Within the following weeks...

My colleague is now leading the project, but I do want to stay available for periodical check-ins. This will be a 2-way street:

I will provide my input when necessary so that I can transfer any useful knowledge.

I will ask how they are performing, specifically where I didn't. I'll ask them detailed questions on their tactics to handle such a complex project with speed. I will seek their advice on decision making and ask about concrete examples of recent decisions.

I will also seek education on the topic internally (trainings, workshops, sessions with more senior colleagues) and externally (courses, books) to learn about productivity, project delivery and decision making

I will create my own speed and decision making framework, which I will apply to all new projects, while documenting situations, decisions and outcomes for reviews.

{TASK + ACTION - Scale: Granular details / Timeframe: Long-term}

For the months to come, I will probably be working on new projects. So I will check-in periodically with my managers and seek feedback from new stakeholders with a focus on the topics of speed and decision making. This will help me "keep my finger on the pulse", and allow me to measure progress.

I will review my personal documentation of decision making to assess improvements, take in lessons from recent decisions, and further improve my own framework so that it becomes a mature, solidified practice.

I will also seek opportunities to transfer this knowledge to other colleagues who may be in the same situation I was, while sharing my own journey of improvement in the area.

{CONTIGENCIES}

Things don't always go accordingly to the plan, and I anticipate that these 2 new issues could happen:

{Problem > Solution 1}

My colleague, who is now in charge of the project, might be struggling with similar issues. This may mean that expectations might be too high (necessitating a push back), or that the project is particularly challenging in that area.

In such a case, I would partner more closely with them so that we can find solutions and learn from the issue at hand together. This should increase speed and accelerate ramp-up for the both of us.

{CONTIGENCIES - Problem 2}

In the long-run, I might also get the feedback (or realise on my own) that my decisions making and ability to move fast aren't improving.

If that's the case, I would conduct another assessment of the skill-gap, seek more detailed and concrete feedback and consider a more personalized training approach like coaching services or seminars.

I tried to write the answer part above in one go, so that it can feel more realistic and less "polished" than a carefully written answer. If yours is within that ballpark, you're definitely equipped to nail open-ended questions at top companies.

Thank you for reading this (very) long post. I hope it was helpful :-)

The last thing I want to say is that all the above concepts are general guidelines. They're here to help you visualize, organize and train, but they're not law, and they are other ways to think about the topic. Once you're comfortable with the key principles, don't obsess over them and start playing with the rules. That's also what great improvisers do 🎸

I wrote several other step-by-step guides like this one, so if you want to learn more about job searching and resume writing, check these out:

You can also request a Free Resume Review (details below).

I wish you all the best with your job search and interviews!

Emmanuel

I'll assess your resume personally.

and write a 3 pages review.

You'll get:

1️⃣ Detailed recommendations on how to improve your CV.

2️⃣ Insider secrets on how your resume is reviewed.

3️⃣ Examples of rewriting for inspiration.